Former US President Barack Obama is resettling in Kenya for at least a year as Special Envoy for US Diplomacy (SED), a deployment which he said “makes me truly grateful as I pay tribute to the land of my father- and forefathers”.

Nominated by President Joe Biden, who was Obama’s Vice President between 2009 and 2016, the former president, codenamed “Renegade”, was confirmed by The US Senate, which is increasingly exploring the possibility of sending retired Presidents to countries of their ancestry.

Obama is expected to jet into the country on June 13 for what his team calls “a reconnaissance trip”, has indicated his desire to set up an office outside the capital Nairobi when he finally lands.

This, he says, will help him better understand devolution and promote coordination among counties before he can seek an enhanced diplomatic partnership between Kenya and the US.

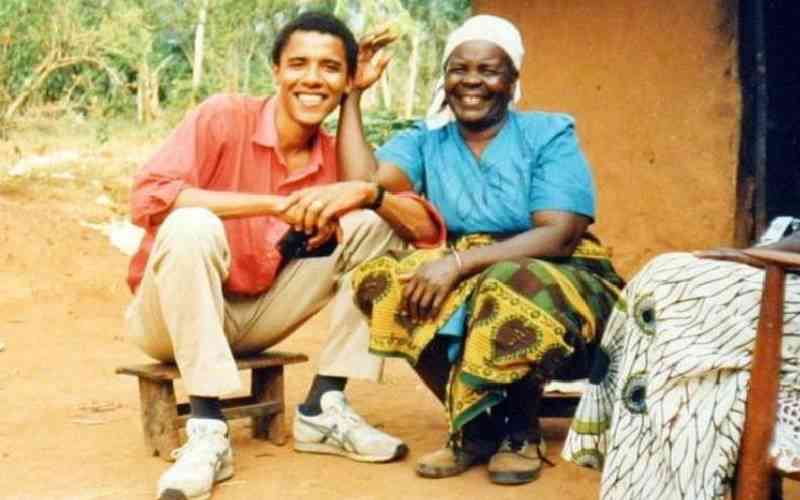

With speculators saying property prices could triple within no time, mooted counties of his stay initially included Siaya, which is the home to Alego, in which sits Kogelo village, where his grandmother (and extended family) have lived for years.

Others were Kajiado, due to its proximity to Nairobi, Lamu and Mandera, where he was expected to see firsthand the intermittent threat of The Al Shabaab, thus better advising the US on best, and prompt, actions to take.

But it is increasingly appearing that Obama could settle in Nyeri with locals noticing a grand, highly secured, ultramodern block, cryptically labelled "Yad Sloof Lirpa" whose use the county government could not disclose, coming up behind Governor Mutahi Kahiga’s official residence. The term is an old time slogan associated with alma mater, Occidental College, Columbia University.

Obama will, however, spend much of his time in Nairobi, where he is expected to shoot his much anticipated documentary “In The Land of My Father”, enlisting, in part, Morgan Freeman and Sir David Attenborough for the narration.

“It has been my lifetime dream to come back to Kenya and to do what our diplomats do here. This is the start of my new, exciting life as a moviemaking expat,” he said, to delirious laughter, in a dinner organised in his honour by The White House last week yesterday.

It is not clear if Obama will be accompanied by his wife Michelle, but sources close to him can confirm that his daughters Malia and Sasha will be in the country and might, for the first time ever, engage in high-level political meetings

.

Obama’s team has said that he is interested in working with local filmmakers and has started reaching out to interested parties to send samples of their work, alongside other professional details.

The Obama mission is believed to have been his own initiative after his 2015 visit to Kenya as president.

His inner circle says that he was “truly impressed” by the potential Kenya has politically and economically and negotiated with President Biden to have this deployment.

“It would have come earlier during (Donald) Trump’s administration but look, that would have been dramatic,” David Axelrod, Obama’s former strategist, said. “He would have been ridiculed by the 45th.”

It is believed the plans to send Obama to Kenya were solidified during President William Ruto’s US December visit, and the subsequent Dr Jill Biden visit to Kenya earlier this year.

Hawk-eyed papparazzi have already spotted Secret Service agents in some of the city’s most expensive haunts, and two Cadillac Escalades spotted at Villa Rosa Kempinski Sunday afternoon further gave credence to early speculation of a top global leader’s expected presence.

Meanwhile, Kenya may explore the possibility of Obama immediately talking to opposition leader Raila Odinga over the ongoing anti-government protests.

Top leadership believes Obama could prevail over the opposition, with an insider saying: “Obama could stop the sun with his words and could calm the ocean with his hands.” By Peter Theuri, The Standard