The government of Kenya on Thursday, February 10, denied claims that it has encroached South Sudan’s territory arguing that it respects the boundaries of its neighbors.

This was after it emerged that South Sudan summoned Kenya’s envoy to Juba, Samuel Nandwa, to protest an alleged encroachment on its territory.

Kenya's Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary, Dr Alfred Mutua, on Thursday told the Nation that Juba had not officially raised the matter with Nairobi hence scanty information on the alleged encroachment.

ALSO READ: Kenya, South Sudan in border dispute

“South Sudan has not communicated to us officially on the matter, therefore, I cannot comment on the issue sufficiently,” Dr Mutua is quoted.

As reported, Kenya’s Foreign Affairs Principal Secretary, Dr Korir Sing’oei, said his country had not encroached on the territory of South Sudan noting that boundary delimitation is currently ongoing under African Union.

“Kenya respects the territorial integrity of all her neighbors and has not encroached on any of their territories. A boundary delimitation process of all borders under the AU is ongoing and is being conducted consultatively and jointly with our neighbors,” said Dr Sing’oei.

“Our Kenya National Boundaries Office (Kenao) is in charge of this process.”

Juba claims that Kenya has “illegally” taken 42 points of its borderline at Nadapal, a settlement on a key crossing point and trade route between the two countries.

South Sudan’s Deputy Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation minister, Deng Dau Deng, said Kenya and Uganda are claiming part of the South Sudan borderline, pointing out that Juba will not cede an inch of the territory.

Deng had said that Juba reported Kenya and Uganda to the African Union over the alleged border encroachment.

Inside the disputed Elemi Triangle

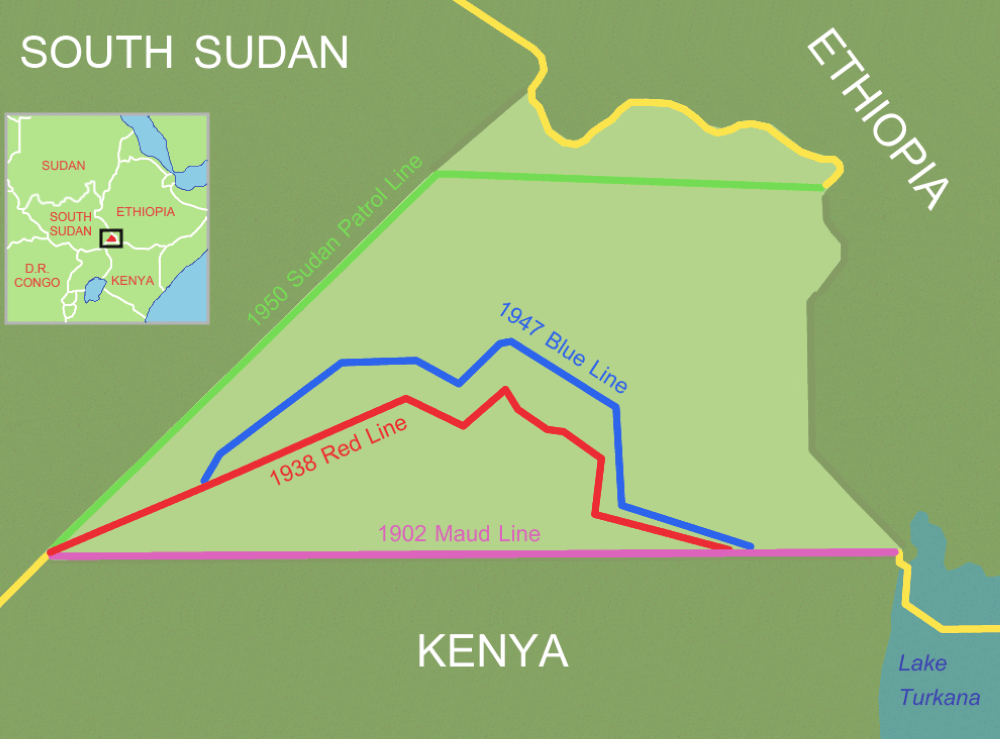

South Sudan and Kenya have a portion of their border, it is reported, largely undetermined at the Ilemi (also called Elemi) Triangle, a sparsely populated area of about 14,000 square kilometres.

The Ilemi Triangle region is at the north-western corner of Lake Turkana, in northern Kenya and on the fringe of southern South Sudan. It is believed to be rich in oil.

In this region, and beyond, pastoral communities have historically engaged in raids on livestock. In the past they used traditional weapons but since the nineteenth century onwards the use of firearms has been common.

In 2012, Tullow Oil, a multinational oil and gas exploration company, discovered oil in the north of Turkana, a Kenyan county.

According to Kenyan media reports, the name Ilemi is believed to be from a famous chief of the Anuak, a community on South Sudan’s boundary with Ethiopia. The triangle was named in honour of chief Ilemi Akwon.

It is home to the Turkana, Didinga, Toposa, Inyangatom and Dassanach communities. These communities are from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan, but they traditionally migrate to the triangle in search of pasture for their animals.

The Turkana are found in South Sudan and Turkana County, while the Didinga are in South Sudan and north eastern Uganda. The Toposa are an ethnic group in South Sudan. The Nyangatom are Nilotic agro-pastoralists inhabiting the border of southwestern Ethiopia, southeastern South Sudan, and the Ilemi Triangle. The Daasanach inhabit parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Sudan.

When the Kenyan Government published a new atlas including part of the disputed Ilemi Triangle within its territory, in 1986, the result was a protest from Khartoum. At the time, there was only one Sudan – before South Sudan formally seceded from Sudan on July 9, 2011.

According to reports, in 1986, the Sudanese Government [Khartoum] believed that the then Sudan People’s Liberation Movement rebels had traded the lands in the Ilemi Triangle with Kenya.

According to reports, the dispute arose from a 1914 treaty in which a straight parallel line was used to divide territories that were part of the British Empire. But, it is noted, the Turkana nomadic herders, among others, continued to move to and from the border freely in search for water and pasture for their animals.

The perceived economic marginality of the land as well as decades of Sudanese conflicts are two factors that could have delayed the resolution of the dispute. The New Times