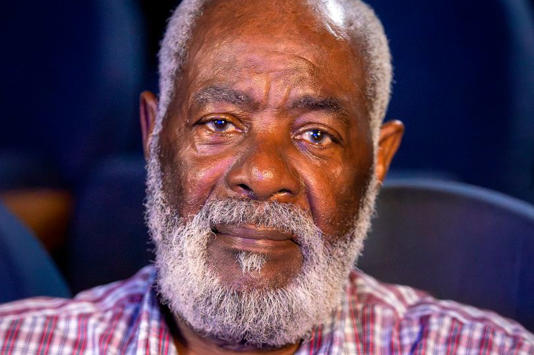

Guy Reid Bailey with Judi Love© Adam Gerrard / Daily Mirror

Brimming with excitement and anticipation, 16-year-old Guy Reid-Bailey came to Bristol ready to start his new life after arriving from his home in Jamaica.

It was 1961, and the UK government was inviting Caribbean workers to Britain to help rebuild a country still recovering from World War II. The very first expats came over in 1948 on the HMT Empire Windrush, but when they got here many had difficulty finding work and housing - black people were often not allowed to go into pubs and dance halls - and if they were, would likely be herded into a separate area.

Walking the streets of Bristol for the very first time, Guy remembers feeling let down by empty promises of a new life as he noticed signs in windows of rooms to let saying: ‘No Blacks, no Irish, no Dogs.’ And when he applied for a job on the Bristol buses in 1963, he wasn’t even given an interview simply because of the colour of his skin.

He was starting to realise this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity wasn’t quite what it was cracked up to be. “When I arrived at the reception of the bus station there was a young lady and she asked me ‘how can I help?” Guy says. “I said ‘I’ve got an appointment at two o’clock’ and she said to the manager ‘your appointment for 2pm is here but he’s black’.

Then the manager said ‘tell him we have no more vacancies’.” This was just one example of the ‘colour bar’ in Britain where some white people discriminated against people of colour denying them jobs and housing. But what happened next changed history.

During the summer of 1963, people of all colours refused to board buses run by the Bristol Omnibus Company because of its refusal to employ black people as drivers or conductors. The Bristol Bus Boycott went on for three months until August 27, when the company announced it would end the colour bar the next day - the same day as Martin Luther King gave his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in Washington DC in the US.

Not only did the 90-day boycott draw national attention to racial discrimination in Britain but it was also influential in the passing of the Race Relations Acts. For Guy, it must have felt surreal to have been such an important part of history?

“I was happy in a sense but not able to show it as I would have liked because of the danger of being attacked by groups of whites including teddy boys and Hells Angels,” he sighs. “They used to attack young black boys and it was heartbreaking to know that the country I came to wasn’t able to protect black people.”

He had three brothers in Jamaica, but told them not to follow him to the UK because “I had to grow up very quickly and I wouldn’t wish my other brothers to experience what I did”. Guy never did become a bus driver, training as a social worker instead.

For over 60 years, Guy has been fighting for people of colour to have the same rights as white people, founding the United Housing Association in 1985 - the first black housing association in Bristol - and setting up the Bristol West Indies Cricket Club (BWICC) because he could see black people weren’t being given the same opportunities in sport.

Earlier this year he was invited to a special screening to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Bristol Bus Boycott at the Watershed in Bristol with Judi Love, comedian and Loose Women panellist, whose parents came to Britain from Jamaica to start a new life. Both Guy and Judi were moved to tears watching archive video footage of the Bristol Bus Boycott on the huge cinema screen set up to commemorate the occasion.

Guy says: ‘My heart moans every time I see those pictures, I shed tears inside. It’s hard to live with. I was sad because in Jamaica if you were black you were given the same opportunities as a white person as long as you had the same education. That’s what drew me to come to England.”

In 2005, Guy was awarded an OBE (the Order of the British Empire) from the Queen at Buckingham Place for his outstanding achievements and service to people in the South West of England. And comedian Judi Love invited him to the Daily Miror’s Pride of Britain awards, with TSB, asking him to represent the Windrush generation when they received a Special Recognition Awards.

His story will also be among those told in a special ITV documentary Pride Of Britain: A Windrush Special this week. “Is this for real?” he says in disbelief. “I can’t believe it, I’m overwhelmed.” Although things have improved over the last 60 years, Guy believes there is still some way to go to stamp out inequality, adding that he can only hope his actions have inspired the younger generation to stand up for their rights.

“The fight is not over, the fight will keep going,” Guy says. “We need younger people to continue to be there for the ones that come after them. What I would like to see is more young people getting involved and not just accepting inequality.”

Judi has nothing but admirations for Guy whose actions helped change the lives of so many people for the better. “My parents came over here with nothing in the late 1950s, early 60s and being Jamaican you just hear the stories, you see the pictures of them coming off the boat looking absolutely stunning in their colourful outfits and the men looking sharp.

“It’s not until I got older that I understood the complexities that came with that. I want to thank Guy for what he’s done, for what he’s contributed. Thank you for changing history and making history for someone like me and people that were born after you. Thank you.” by Jackie Annett , Daily Mirror