In July 2025, Uganda’s courts swiftly dismissed a petition challenging the legality of polygamy, citing the protection of religious and cultural freedom. For most social scientists and policymakers who have long declared polygamy a “harmful cultural practice,” the decision was a frustrating but predictable setback in efforts to build healthier and more equal societies.

In the vast majority of cases, polygamy takes the form of one husband and multiple wives – more precisely referred to as polygyny, originating from the Greek words “poly” (“many”) and “gynē” (“woman or wife”). The opposite arrangement of one wife and multiple husbands is referred to as polyandry (from “anēr” meaning “man” or “husband”) and is exceedingly rare worldwide.

Critics of polygyny present two main arguments. First, they contend it squeezes low-status men out of the marriage market, fostering social unrest, crime and violence against women by frustrated unwed men. Second, it harms women and children by dividing limited resources among more dependents.

This logic has led leading political scientist Rose McDermott to describe polygyny as evil. Other researchers, such as anthropologist Joseph Henrich, even go as far as to credit Christianity’s derision of polygyny as a driving force of Western prosperity.

However, a trio of new studies, all relying on the highest standards of data analysis, contend that these arguments are misguided.

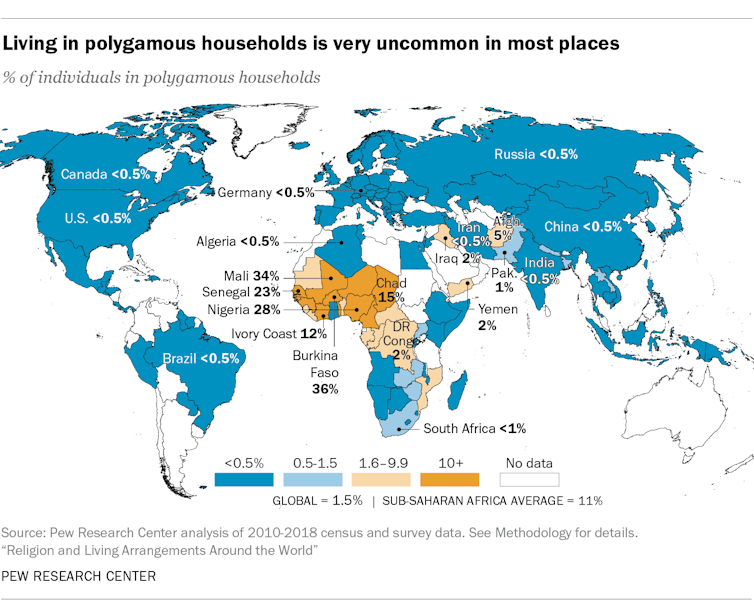

I have spent my career working at the intersection of anthropology and global health, researching how and why family structure varies – and what this diversity means for human well-being. Much of this work has been carried out with colleagues in Tanzania where, like Uganda, polygyny is relatively common. This new wave of work underscores the value of our research, effectively demonstrating that good intentions and intuition are no substitute for cultural sensitivity and evidence.

Does polygyny lock men out of marriage?

A new study published in October 2025 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents the first comprehensive, large-scale analysis of polygyny and men’s marriage prospects. The project is a collaboration between demographer Hampton Gaddy and evolutionary anthropologists Rebecca Sear and Laura Fortunato.

The researchers drew on demographic modeling and an extraordinary trove of census data – over 84 million records from 30 countries in Africa, Asia and Oceania, plus the entire U.S. census from 1880, when polygyny was practiced in some American communities. They demonstrate that polygyny does not lock large numbers of men out of marriage. In fact, in many contexts, men are actually more likely to marry where polygyny is common than where it is rare.

The narrative that polygyny leads to lonely bachelors is intuitive. In a community with equal numbers of men and women, if one man marries two wives, then another man must remain unmarried. Expand that across a whole society, and polygyny looks like a recipe for an army of resentful, single men.

Parallel arguments have been made about the rise of incel – a portmanteau of “involuntary” and “celibate” – subcultures within monogamous nations, including the U.S. Here, the argument is that high-status men leave low-status men sexless and frustrated, ultimately leading to violence.

The trouble is that real demography is not so simple. Women typically live longer than men, men frequently marry younger women, and populations in many parts of the world are growing, ensuring younger spouses are available for older cohorts. These factors, which are characteristic of many contemporary African nations, tilt the marriage market toward a surplus of women. Under many realistic conditions, a sizable proportion of men can have multiple wives without leaving their peers out in the cold.

In fact, in nearly half of the countries examined, higher rates of polygyny were associated with fewer, not more, unmarried men. Only a handful of countries showed the expected positive relationship, and even then inconsistently over time.

The case of historical Mormon communities in North America is equally revealing. When the researchers compared counties with documented Mormon polygyny to others in the 1880 census, they found lower rates of unmarried men in polygynous areas. Gaddy and his colleagues contend that this is explained by the tendency for cultural norms that favor polygyny to also be relatively pronatalist, driving marriage rates upward for all.

Do women and children get a smaller share?

What about the argument that polygyny harms women and children by dividing male-owned wealth among more mouths to feed? There certainly are studies that have demonstrated associations between polygyny and poor health. But another line of thinking argues that correlation should not be equated with causation.

Ten years ago, my colleages and I documented that polygyny is associated with higher food insecurity and poor child health when comparing outcomes across over 50 Tanzanian villages. However, this pattern was an artifact of polygyny being most common in marginalized Maasai communities, which tend to live in drought-prone areas with inadequate health care. Moreover, when comparing families within communities, polygynous households were typically wealthier, a key factor in making polygyny attractive to women, and children were not disadvantaged.

Echoing these results, anthropologist Riana Minocher and her colleagues recently published a study that uses a detailed, longitudinal dataset from a 20-year prospective study in another region of Tanzania. Analyzing survival, growth and education for thousands of children, they found no evidence that monogamous marriage is advantageous.

Together, these results support a theory known as the polygyny threshold model. Simply put, provided women have choice in marriage, sharing a husband is unlikely to be economically detrimental, since they will prioritize marrying men with sufficient wealth to offset any cost. This scenario may not fit all contexts, but these studies clearly undercut claims that polygyny is unequivocally harmful.

Hidden advantages of polygyny

Another recent study, published in August 2025 by economist Sylvain Dessy and his colleagues, goes further, suggesting that polygyny has unrecognized advantages when times are tough.

Drawing on crop yield data from over 4,000 farm households across Mali, census data on marriage patterns and detailed meteorological records, they found that in villages where polygyny is rare, droughts cut harvests dramatically. But in villages where polygyny is common, that blow is softened.

The researchers argue that polygynous marriage, by increasing the number of in-laws, creates stronger networks of social support. Furthermore, with wives often coming from different villages and regions, extended kin are well positioned to send food, money or labor when local crops fail. Such support helps to explain both the resilience of polygynous communities during drought and the continued endurance of the marriage practice from one generation to the next.

So, is polygyny harmless?

These studies don’t mean that polygyny is harmless. Indeed, allowing men but not women to have multiple spouses is clearly unequal and entwined with patriarchal ideology that positions women as subordinate or inferior to men. Recent studies, for example, have suggested that polygynous marriages are more prone to intimate partner violence.

In short, there remain multiple ways polygyny can be harmful.

Nevertheless, the best evidence suggests that polygyny is unlikely to be a root cause of social unrest. Moreover, within wider patriarchal systems that afford few women, regardless of marital status, economic and social security, polygyny may not just be a tolerable choice but in some contexts a preferred arrangement with tangible benefits for both genders.

Simplistic stories about the dangers of polygyny can be compelling and intuitive, but they risk misleading the public, reinforcing stubborn notions of Western cultural superiority and disrupting effective global health policy by sidelining more pertinent initiatives. Building healthier societies necessitates paying attention to the evidence and remaining open to the possibility that all family structures have capacity to cause harm. The Conversation